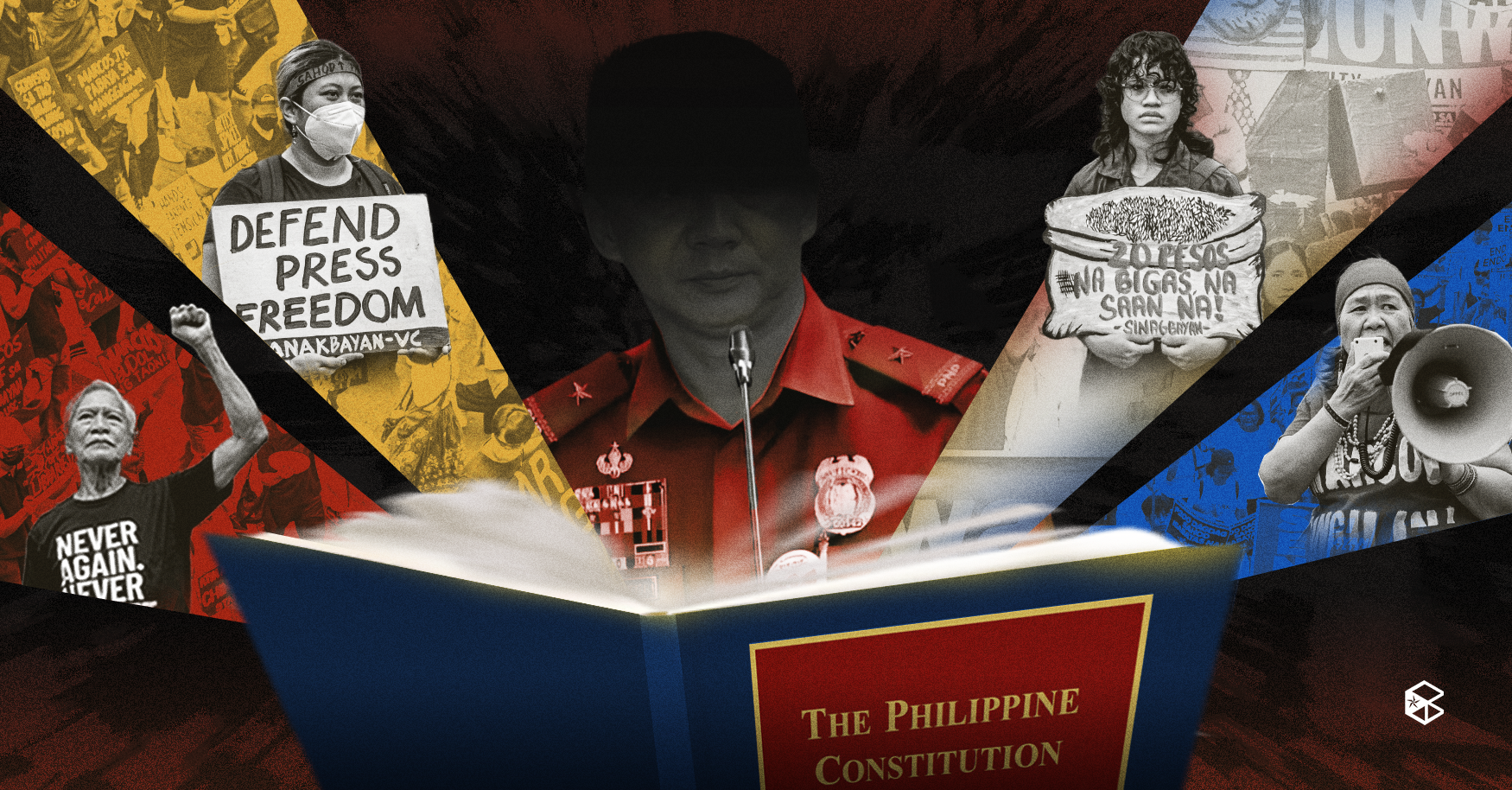

The Philippines continues to suffer under a government mired in corruption. Yet worse than the plundered wealth is the deliberate attempt to stifle voices, as if the lessons of Sept. 21 have long been forgotten.

Even before Sarah Discaya’s appearance before the Senate Blue Ribbon Committee, a series of events had already begun to unfold. From the State of the Nation Address of President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. where he ordered an investigation into alleged corruption in flood control projects, the spotlight has now shifted to the Philippine National Police (PNP). Under the leadership of PNP Chief Gen. Jose Melencio Nartatez Jr., the force has vowed to strictly enforce the “no permit, no rally” policy by putting bureaucratic barriers on a constitutional right and raising fears that dissent is once again being pushed to the margins.

Yet the clamor and resistance persist, grounded not in defiance alone but in the freedoms safeguarded by the Philippine Constitution.

Embedded in law and history

The right to peaceful assembly is not a gift from the government but a guarantee embedded in the 1987 Philippine Constitution. Under Article III, Section 4 states, “No law shall be passed abridging the freedom of speech, of expression, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and petition the government for redress of grievances.”

It is a safeguard against tyranny, enshrined so that citizens can freely gather, speak, and demand accountability without fear of reprisal. When state forces reduce this right to a matter of permission, they forget that the Constitution recognizes it as inherent and fundamental.

At the same time, Batas Pambansa Blg. 880, or the The Public Assembly Act of 1985, often invoked to justify the “no permit, no rally” policy, has itself been misused. But even the law itself is regulatory, not prohibitive. Its intent is to manage the time, place, and manner of assemblies, not to suppress them. Moreover, it was never meant to silence voices critical of those in power. When authorities twist its intent, they weaponize bureaucracy against democracy.

History has shown what happens when dissent is suppressed, corruption thrives, abuses multiply, and the people suffer in silence. The Philippines need not repeat the mistakes of martial law to learn its lesson again. What must endure is the recognition that the freedom to assemble is not a privilege to be granted, but a right that has always been, and must remain, beyond the reach of those in power. While the permit remains an issue, the voices remain stronger.

Do we hear the people sing?

On Sept. 21, the People Power Monument became witness once again to the voices of the people. The emergence of the Trillion People March and Billion People March reflects the depth of public frustration over systemic corruption. The names are simple as it directly points to ₱1.9 trillion ($33.27 billion) allocated on flood control over the past 15 years, much of which has been lost to corruption.

Trillion People March spokesperson Francis Aquino Dee said the protest is expected to gather over 15,000 Filipinos for their demand for accountability. Permits have been filed and coordination with police secured. Yet the moral authority of this gathering lies not in paperwork but in the urgency of its cause.

For many, the nation’s anger has reached its breaking point. “The people’s anger is at boiling point. The anger is overflowing,” said Akbayan Rep. Perci Cendaña, stressing that this rage must be channeled into action that is both constructive and relentless in its defense against corruption. Moreover, the struggle transcends colors and beliefs as Bishop Efraim Tendero called on Filipinos “to set aside differences and unite in the spirit of EDSA.” The present is no longer just an issue but a fight to save our future from corruption and impunity.

Yet the protest is not only about the issues and scandal surrounding the political arena now. Every Sept. 21, Filipinos confront the very memory of martial law, one never forgotten, one that must be spoken. Based on Amnesty International, they recorded more than 107,000 victims. Over 70,000 to 72,000 were imprisoned, 34,000 were tortured and 3,240 were killed from the period of 1972 to 1981. So to march now is not just for the present, but for those who bravely fought in the past and were under the strict authority of a dictator.

But now, we transcend mere beliefs. The Philippines has long been known as a resilient nation, but for how long can we repress anger fueled by the incompetence of the very government meant to serve the people, not their own lust for power and wealth?

We are ready, now more than ever. Not divided by belief nor branded by colors, but united because we are Filipinos.